I was asked at a Racial Justice conference in November 2023 if I would put together a bibliography on Indigenous Justice and theology, and so here it is. Rather than just give the bare references, I have included annotations.

This list is derived from the bibliography created for my dissertation Unsettling Theology: The Theological Legacy of the Indian Residential Schools of Canada 1880-1970, which was submitted in an amended form to the University of London in April 2021. These are the documents, articles, and books that, in the second part of the dissertation, allowed me to draw an outline of theological ideas that justified colonization, slavery, and genocide. It includes works on anthropology, sociology, pedagogy, research methods, as well as discussions of racism, slavery, decolonization, and post-colonial theory. The bibliography also includes some works of Indigenous theology and those allied with Indigenous justice activists which I used in the third part of my dissertation. I have removed the texts on other matters that my dissertation dealt with, such as the philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1995) (that was the focus of the first part) and kenotic theology (which was the theme of the third part). I think most of the hyperlinks are active, but let me know if one becomes dead.

Alexander VI, Intera caetera from https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Inter_Caetera, accessed January 17, 2017. This is the famous bull from Pope Alexander VI in which he draws a line between Portugal and Spain as they discover and conquer new lands.

Alfred, Taiaiake, Peace, Power, Righteousness: An Indigenous Manifesto, Second Edition (Don Mills/Toronto ON: Oxford University Press, 2009).

Anglican Video, https://www.anglican.ca/primate/tfc/drj/doctrineofdiscovery/ (Toronto ON: The Anglican Church of Canada, 2019). This is a good video about the Doctrine of Discovery.

Aristotle, Politics 1254b-1255a translated by Benjamin Jowett (Oxford UK: Clarendon Press, 1885). This is the passage in which Aristotle justifies slavery.

Atwood, Margaret, Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature (Toronto: House of Anansi, 1972). An old but still relevant review of Canadian literature, largely adhering to the “garrison mentality” of Canadians, in which authors typically viewed the land and indigenous peoples as threatening and unforgiving.

Barrera, Jorge, “Author Joseph Boyden’s shape-shifting Indigenous identity”, at https://aptnnews.ca/ 2016/12/23/author-joseph-boydens-shape-shifting-Indigenous-identity/ accessed April 23, 2021. Joseph Boyden is a prize-winning Canadian author who falsely claimed to have an indigenous background.

Battiste, Marie, Decolonizing Education: Nourishing the Learning Spirit (Saskatoon SK: Purich Publishing Limited, 2013).

Beaudoin, Gérald A. , & Michelle Filice, “Delgamuukw Case”, The Canadian Encyclopedia, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/ delgamuukw-case, accessed December 9, 2018. Delgamuukw is the key case establishing “aboriginal title”.

Berger, Thomas W., A Long and Terrible Shadow: White Values, Native Rights in the Americas since 1492 (Vancouver: Douglas & MacIntyre, 1999).

Bevans, Stephen, “From Edinburgh to Edinburgh: Toward a Missiology for a World Church” in Mission after Christendom: Emergent Themes in Contemporary Issues (Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), pp. 1-11. I include a number of books from and about the 1911 World Missionary Conference in Edinburgh because it is a snapshot of the state of mind of missionaries at that time.

Biggar, Nigel, Ethics and Empire, http://www.mcdonaldcentre.org.uk/ethics-and-empire, accessed January 31, 2018. Biggar is a Church of England priest and theologian who is trying to defend Britain’s colonial history.

——————, “Don’t feel guilty about our colonial history” The Times, November 30, 2017 https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/don-t-feel-guilty-about-our-colonial-history-ghvstdhmj, accessed January 31, 2018.

Blackburn, Carole, Harvest of Souls: The Jesuit Mission and Colonialism in North America 1632-1650 (Montreal QC & Kingston ON: McGill-Queens University Press, 2000). This is a brilliant book.

Brean, Joseph, “Cultural genocide’ of Canada’s indigenous peoples is a ‘mourning label,’ former war crimes prosecutor says”, National Post, January 15, 2016, http://news.nationalpost.com/news/canada/cultural-genocide-of-canadas-indigenous-people-is-a-mourning-label-former-war-crimes-prosecutor-says, accessed May 22, 2017.

Brébeuf, Jean de, “‘Twas in the Moon of Wintertime” translated by Jesse Edgar Middleton, Hymn 146 in Common Praise: Anglican Church of Canada (Toronto ON: Anglican Book Centre, 1998). For Wyandot/Huron original see “Huron Carol Translation With Pronunciation Guide” at https://penguinpoweredpiano.wordpress.com/2013/05/03/song-translation-huron-carol-by-heather-dale-huronwendat-and-canadian-french/ accessed 26 April 2021. Every Canadian child probably learned this hymn.

Brett, Mark G., Decolonizing God: The Bible in the Tides of Empire (Sheffield UK: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2009).

Brown, Stewart J., Providence and Empire, 1815-1914 (London: Routledge, 2013).

Canada’s Missionary Congress: Addresses Delivered at the Canadian National Missionary Congress, Held in Toronto, March 31 to April 4, 1909, with Reports of Committees (Toronto ON: Canadian Council, Laymen’s Missionary Movement, 1909).

CBC News (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation), “A timeline of residential schools, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission”, http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/a-timeline-of-residential-schools-the-truth-and-reconciliation-commission-1.724434, accessed October 23, 2017.

Carleton, John, “John A. Macdonald was the real architect of residential schools” The Toronto Star, July 9, 2017, from https://www.thestar.com/opinion/commentary/2017/07/09/john-a-macdonald-was-the-real-architect-of-residential-schools.html, accessed April 22, 2021. John A. Macdonald was the founding Prime Minister of Canada.

Carlson, Keith Thor, The Power of Place, The Problem of Time: Aboriginal Identity and Historical Consciousness in the cauldron of Colonialism (Toronto ON: University of Toronto Press, 2010).

Carruthers, Amy, Kevin O’Callaghan, and Madison Grist, “Canada: Federal Government Introduces UNDRIP Legislation” 16 December 2020, at https://www.mondaq.com/canada/indigenous-peoples/1016528/federal-government-introduces-undrip-legislation%20accessed%20April%2022, accessed April 22, 2021. UNDRIP is the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007).

Castro, Daniel , Another Face of Empire: Bartolomé de Las Casas, Indigenous Rights, and Ecclesiastical Imperialism (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2007). Bartolomé de las Casas (1484-1556) was a Dominican Friar and Roman Catholic Bishop who was the first person to effectively object to the Spanish Crown that the Spanish Conquest of Mexico and other parts of the “New World” was problematic and injurious to indigenous peoples and the truth of the gospel. He famously engaged in a debate with Juan Ginés Sepúlveda in 1550 on Indigenous rights, colonization, and evangelism.

Charles, Mark and Soong-Chan Rah, Unsettling Truths: The Ongoing Dehumanizing Legacy of the Doctrine of Discovery (Downers Grove IL: InterVarsity Press, 2019). This is co-written by Mark Charles, a Navaho man who comes from an Evangelical perspective.

Christophers, Brett, Positioning the Missionary: John Booth Good and the Confluence of Culture in Nineteenth-Century British Columbia (Vancouver BC: University of British Columbia Press, 1998). John Booth Good was an Anglican priest who established a mission to the Nlha7kápmx on the Fraser River near what is now Lytton.

Coates, Ken, “McLachlin said what many have long known”, The Globe and ail, May 29, 2015 https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/mclachlin-said-what-many-have-long-known/article24704812/, accessed May 22, 2017. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada calls the “Indian Residential Schools” a kind of genocide.

Cone, James, “Whose Earth Is It Anyway?” in Earth Habitat: Eco-Justice and the Church’s Response, eds. Dieter Hessel and Larry Rasmussen (Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press, 2001). James Cone (1938-2018) was an American theologian who created the discipline of Black Theology.

——————, “God and Black Suffering: Calling the Oppressors to Account”, The Anglican Theological Review, Volume 90:4 (Fall 2008), pp. 701-712.

——————, The Cross and the Lynching Tree (Maryknoll NY: Orbis Books, 2011).

Cooper, James Fennimore, The Last of the Mohicans, A Narrative of 1757 (originally published in 1826) in James Fenimore Cooper: The Leatherstocking Tales Vol. 1 (LOA #26) (New York NY: The Library of America, 1985). One of the myths in the 19th century is that the Indigenous peoples where disappearing because of illness, war, and assimilation. This novel is an example of the myth. Some 3000 Mohicans are still very much in existence in upstate New York and western Massachusetts.

Culhane, Dara, The Pleasure of the Crown Anthropology, Law and First Nations (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 1998).

Darymple, William, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company (London UK: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019). This history clarifies how the East India Company ravaged India in search of profits.

Daschuk, James, Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life (Regina SK: University of Regina Press, 2013). A somewhat controversial history laying out how epidemics in 19th century western Canada resulted in the movement of various First Nations and the ease of British colonists in taking the land.

Deloria, Jr, Vine, God is Red: A Native View of Religion, Second Edition (Golden CO: North American Press, 1992). An eccentric pioneering work. Deloria was the son and grandson of Lakotan Episcopalian priests and himself studied with Lutherans in Chicago. While given to sweeping essentialist claims about both Christianity and “Native American Religion”, he was among the first to identify the destructive effects of Christian evangelism among Indigenous peoples in what became the USA and Canada.

Diamond, Jared, Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 1997). Why did the Europeans “discover” and “conquer” the world, and not Asians, Africans, pre-Columbian Indigenous peoples in the Americas, or Pacific islanders? This book examines the influence of geography and the availability of domesticated species on history.

Diocese of New Westminster, Monthly Record 1889, 1890, 1893, 1894, 1895. Archives of the Diocese of New Westminster, Vancouver BC. I used the archives to verify some theses arising out of secondary literature.

Dixon, David, Never Come to Peace Again: Pontiac’s Uprising and the Fate of the British Empire in North America (Norman OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2005).

Dodds Pennock, Caroline, “Mass Murder or Religious Homicide? Rethinking Human Sacrifice and Interpersonal Violence in Aztec Society”, Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung, Vol. 37, No. 3 (141), Controversies around the Digital Humanities (2012), pp. 276-302. One of Sepulveda’s arguments against Bartolomé de las Casas was that the practice of human sacrifice by the Aztecs required an intervention by the Spanish Crown. This sociological work re-casts human sacrifice as a more common practice than is often admitted, and formulates a theory that it reinforces structures in society.

Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne, Loaded: A Disarming History of the Second Amendment (San Francisco CA: City Lights Books, 2018). This book makes the argument that the Second Amendment of the US Constitution, the right to bear arms, is an endorsement of the right of “white” persons to organise and “defend” themselves against African-American slave uprisings and Indigenous peoples’ attacks.

Dussel, Enrique, A History of the Church in Latin America, Colonialism to Liberation (1492-1979) translated and revised by Alan Neely (Grand Rapids MI: William B, Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1981).

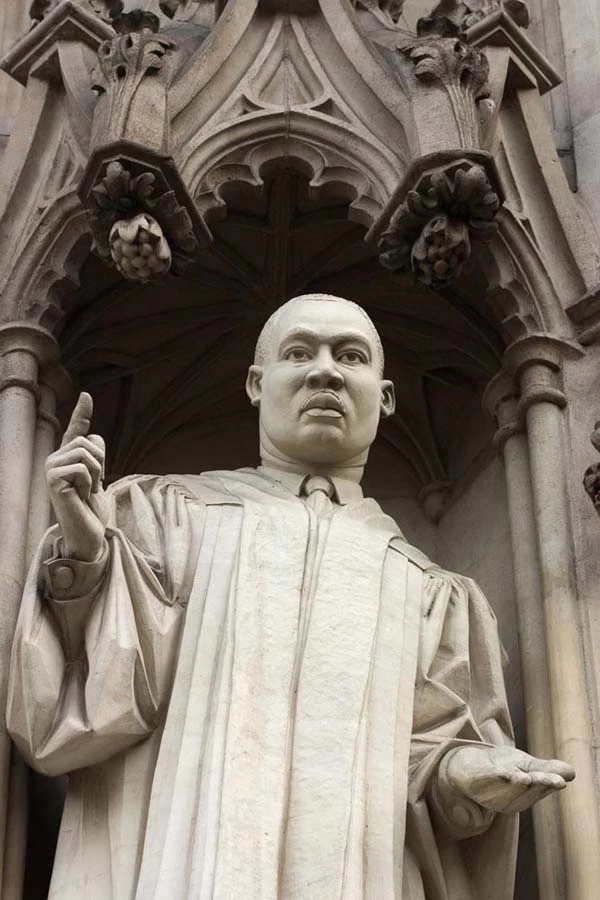

Edmondson, Mika, The Power of Unearned Suffering: The Roots and Implications of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Theodicy (Lanham MD: Lexington Books, 2017).

Ellis, Ian M., A Century of Mission and Unity: A Centenary Perspective on the 1910 Edinburgh World Missionary Conference (Dublin IE: The Columba Press, 2010).

Fanon, Frantz, The Wretched of the Earth translated by Cobstance Farrington (Harmondsworth UK: Penguin Books, 1967). This is one of the classics of Decolonial texts.

Ferguson, Niall, Civilization: The West and the Rest (New York NY: Penguin Books, 2011). Ferguson writes a biased history justifying the pre-eminence of the West.

Fernandez, Manuel Giménez “Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas: A Biographical Sketch” in Bartolomé de Las Casas in History: Toward an Understanding of the Man and His Work edited by Juan Friede and Benjamin Keen, (DeKalb IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1971), pp. 67-126.

Fisher, Robin, “Review of Tom Swanky, The True Story of Canada’s “War” of Extermination on the Pacific plus the Tsilhqot’ in and Other First Nations Resistance” in BC Studies 182 (Summer 2014), pp. 217-218.

François 1er (France), Commission à Jacques Cartier pour l’établissement du Canada, 17 octobre 1540, from https://biblio.republiquelibre.org/Commission_de_Fran%C3%A7ois_1er_%C3%A0_Jacques_Cartier_pour_l’%C3%A9tablissement_du_Canada,_17_octobre_1540, accessed February 14, 2016.

Gagnon, Lysiane, “McLachlin’s comments a disservice to her court, and to aboriginals”, The Globe and Mail, Jun. 10, 2015 https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/mclachlins-comments-a-disservice-to-her-court-and-to-aboriginals/article24879482/, accessed May 22, 2017.

Geddes, Gary, Medicine Unbundled: A Journey Through the Minefields of Indigenous Health Care (Victoria BC: Heritage House Publishing Company Limited, 2017).

Gilley, Bruce, “The Case For Colonialism”, Third World Quarterly, 2017 at https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1369037 (accessed January 31, 2018). A notorious article justifying 500 years of European colonialism.

Gottschalk, Peter, Religion, Science, and Empire: Classifying Hinduism and Islam in British India (Oxford UK: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Grant, John Webster, Moon of Wintertime: Missionaries and the Indians of Canada in Encounter since 1534 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984).

Grau, Marion, Rethinking Mission in the Postcolony: Salvation, Society and Subversion (London UK: T&T Clark, 2011).

Gray, Robert, A Good Speed to Virginia (London England: William Welbie, 1609), quoted in John Parker, “Religion and the Virginia Colony 1609-10” in The Westward Enterprise: English Activities in Ireland, the Atlantic, and America 1480-1650 edited by K. R. Andrews, N. P. Canny, and P. E. N. Hair (Liverpool UK: Liverpool University Press, 1978), pp. 245-270.

Guyatt, Nicholas, Providence and the Invention of the United States, 1607–1876 (Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Hanke, Lewis, All Mankind is One: A Study of the Disputation Between Bartolomé de Las Casas and Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda in 1550 on the Intellectual and Religious Capacity of the American Indians (DeKalb IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1974).

Heinrichs, Steve, editor, Buffalo Shout, Salmon Cry: Conversations on Creation, Land Justice, and Life Together (Waterloo ON: Herald Press, 2013).

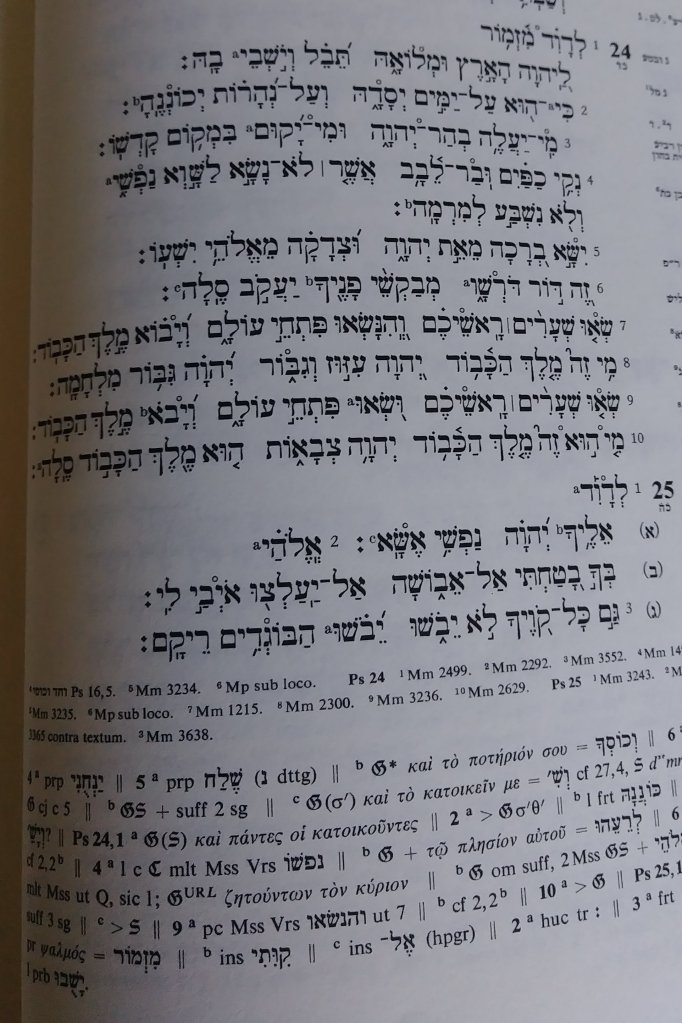

——————, editor Unsettling the Word: Biblical Experiments in Decolonization (Maryknoll NY: Orbis Books, 2018).

Henry VII (England), Letters Patent to John Cabot , 5 March 1496 from http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Maritime/Sources/1496cabotpatent.htm, accessed January 20, 2017.

Higham, Carol L., Noble, Wretched, & Redeemable: Protestant Missionaries to the Indians in Canada and the United States, 1820-1900 (Albuquerque NM: University of New Mexico Press & Calgary AB: University of Calgary Press, 2000). A brilliant study.

Hills, George (1st Bishop of British Columbia), Columbia Mission Special Fund (London, 1860), Archives of the Diocese of New Westminster, Vancouver BC.

Idle No More website. http://www.idlenomore.ca/, accessed October 29, 2018.

Indigenous Reporters Program of Journalists for Human Rights, Style Guide for Reporting on Indigenous People (December 2017), 1-8, http://icht.ca/style-guide-for-reporting-on-indigenous-people/, accessed January 10, 2018.

Jones, Evan T., and Margaret M. Condon, Cabot and Bristol’s Age of Discovery: The Bristol Discovery Voyages 1480-1508 (Bristol UK: University of Bristol, 2016),

Joseph, Bob, 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act: Helping Canadians Make Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples a Reality (Port Coquitlam BC: Indigenous Relations Press, 2018).

Kampen, Melanie, Unsettling Theology: Decolonizing Western Interpretations of Original Sin, Unpublished MTS thesis (Waterloo ON: Conrad Grebel College in the University of Waterloo, 2014).

Kan, Sergei, Memory Eternal (Seattle WA: University of Washington Press, 1999). This is a fascinating history of the Russian Orthodox mission to the Tlingit people of what is now the Alaskan panhandle, and how the Tlingit became more Orthodox when Russia transferred Alaska to the United States.

Keddie, Grant, Songhees Pictorial: A History of the Songhees People as seen by Outsiders 1790 – 1912 (Victoria: Royal BC Museum, 2003). The Songhees were the people who inhabited (and continue to live in) what became Victoria, British Columbia, where most of my dissertation was written.

Khan, Sahar, “The Case Against “The Case for Colonialism”” (at https://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/case-against-case-colonialism, accessed January 31, 2018).

King, Thomas, The Truth About Stories (Toronto ON: House of Anansi Press, 2003). Tom King is one of the funniest commentators on the situation of Indigenous peoples in North America. A good introduction if one is new to the topic.

——————, The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America (Toronto ON: Doubleday Canada, 2012).

Klassen, Pamela E., The Story of Radio Mind: A Missionary’s Journey on Indigenous Land (Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press, 2018). The story of the eccentric Frederick Du Vernet, Archbishop of Caledonia in northeastern British Columbia, among the Ts’msyen, Nisga’a, and Haida.

Lagace, Naithan and Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair, “The White Paper, 1969”,

The Canadian Encylopedia, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/ en/article/the-white-paper-1969, accessed December 9, 2018. The White Paper of 1969 argued for the abolition of the Indian Act and the full assimilation of Indigenous peoples into the majority settler population of Canada. The opposition to this marks the rise of Indigenous rights in Canada.

Lalemant, S.J., Jérôme in Jesuit Relations 20:71, in Carole Blackburn, Harvest of Souls: The Jesuit Mission and Colonialism in North America 1632-1650 (Montreal QC & Kingston ON: McGill-Queens University Press, 2000).

Las Casas, Bartolomé de, In Defense of the Indians translated and edited by Stafford Poole (DeKalb IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1974), quoted in Lewis Hanke, All Mankind is One: A Study of the Disputation Between Bartolomé de Las Casas and Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda in 1550 on the Intellectual and Religious Capacity of the American Indians (DeKalb IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1974).

Le Jeune SJ, Paul. Jesuit Relations 5:177 in Carole Blackburn, Harvest of Souls: The Jesuit Mission and Colonialism in North America 1632-1650 (Montreal QC & Kingston ON: McGill-Queens University Press, 2000).

Lemkin, Raphael, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation – Analysis of Government – Proposals for Redress (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1944), p. 79, quoted in Haifa Rashed & Damien Short “Genocide and settler colonialism: can a Lemkin-inspired genocide perspective aid our understanding of the Palestinian situation?”, The International Journal of Human Rights, 16:8, (2012), 1142-1169; p. 1143. This was the book that first used the term “genocide”.

Losada, Ángel, “The Controversy between Sepúlveda and Las Casas in the Junta of Valladolid” in Bartolomé de Las Casas in History: Toward an Understanding of the Man and His Work, edited by Juan Friede and Benjamin Keen (DeKalb IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1971), pp. 279-308.

MacDonald, David B. & Graham Hudson, “The Genocide Question and Indian Residential Schools in Canada” in Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique 45:2 (June/juin 2012), 427-449; p. 433.

MacDonald, Jake, “How a B.C. native band went from poverty to prosperity”, The Globe and Mail, Report on Business Magazine, May 29, 2014, updated June 19, 2017, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/rob-magazine/clarence-louie-feature/article18913980/, accessed July 28, 2018.

McEachern, Allan, Delgamuukw v British Columbia quoted in in Delgamuukw v. BC, Supreme Court of Appeal, June 25, 1993 [210] https://www.courts.gov.bc.ca/jdb-txt/ca/93/04/1993bcca0400.html, accessed November 21, 2018.

Mackey, Eve, “Unsettled Expectations: Uncertainty, Land and Settler Decolonization (Black Point NS: Fernwood Publishing, 2016).

McInnis, Edgar, Canada: A Political and Social History, Third Edition (Toronto ON: Holt, Rinehart and Winston of Canada, Limited, 1969). This was a classic textbook that hewed to the “disappearing Indian” mythology, barely mentioning Indigenous peoples after the middle of the 19th century.

McMillan, Allan D. Native Peoples and Cultures of Canada, 2nd ed. (Vancouver BC: Douglas & McIntyre, 1995).

Mann, Charles C., 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, 2nd Edition (New York NY: Vintage Books/Random House, 2011). This is a brilliant summary of archaeology, sociology, anthropology, and other fields of work done on the Americas before 1492. Another good introduction.

Manuel, Arthur & Ron Derrickson, Unsettling Canada: A National Wake-Up Call (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2015).

Marshall, John, Johnson v. M’Intosh 21 U.S. (8 Wheat.) 543 (1823) at https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/21/543/#tab-opinion-1922743 accessed July 29, 2020. The cornerstone of US property law, this case was the first in American jurisprudence to identify “The Doctrine of Discovery”.

M’baye, Babacar “The Economic, Political, and Social Impact of the Atlantic Slave Trade on Africa” European Legacy (2006), 11:6, pp. 607-622.

Menocal, María Rosa, The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain (New York NY: Back Bay Books/Little, Brown and Company, 2002). A bit of an idealised history, it nevertheless demonstrates the greater degree of multiculturalism and tolerance that was in existence in Spain before the Reconquista.

Michalopoulos, Stelios and Elias Papaioannou, “The Long-Run Effects of the Scramble for Africa”, The American Economic Review, July 2016, Vol. 106, No. 7, pp. 1802-1848.

Miller, J. R., Shinguak’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools (Toronto ON: University of Toronto Press, 1996).

——————, Skyscrapers Hide The Heavens: A History of Native-Newcomer Relations in Canada, 4th Edition (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018).

Milloy, John S., A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School System 1879-1986 (Winnipeg MB: The University of Manitoba Press, 1999).

Monchalin, Lisa, The Colonial Problem: An Indigenous Perspective on Crime and Justice in Canada (Toronto ON: University of Toronto Press, 2016). Like many lands where the settlers outnumber the Indigenous population, the incarcerated population of Indigenous is out of proportion to their part in the nation’s population; this argues that the criminal justice system is structurally biased against them.

Moore, Dene, “B.C. First Nations mark small pox anniversary” published in Metro News/Canadian Press, August 06 2012, http://www.metronews.ca/news/canada/2012/08/06/b-c-first-nations-mark-small-pox-anniversary.html, accessed January 16, 2017.

Morton, Desmond, A Short History of Canada, Fifth Edition (Toronto ON: McClelland & Stewart Ltd., 2001). Another very-euro-centric history of Canada.

Mott, John H., The Decisive Hour of Christian Missions (Toronto ON: The Missionary Society of the Methodist Church, The Young People’s Forward Movement Department, 1910). John Mott was the moving force behind the 1910 World Missionary Conference in Edinburgh.

Newcomb, Steven T., Pagans in the Promised Land: Decoding the Doctrine of Christian Discovery (Golden CO: Fulcrum Publishing, 2008). Newcomb, a Shawnee/Lenape legal scholar, deconstructs the Christian origins of the Doctrine of Discovery.

Nicholas V, Dum Diversas from http://unamsanctamcatholicam. blogspot.ca/2011/02/dum-diversas-english-translation.html, accessed January 17, 2017.

——————, Romanus Pontifex, from http://www.nativeweb.org/pages/legal/indig-romanus-pontifex.html, accessed January 17, 2017.

Niezen, Ronald, Truth and Indignation: Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission on Indian Residential Schools, Second Edition (Toronto ON: University of Toronto, 2017). The first major work examining the effects of the Canada’s Truth & Reconciliation Commission on Residential Schools.

Nunn, Nathan, ‘The Long-term Effects of Africa’s Slave Trades’’ The Quarterly Journal of Economics (2008) 123, pp. 139–76.

Parkinson, Robert G., The Common Cause: Creating Race and Nation in the American Revolution (Chapel Hill NC: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture and the University of North Carolina Press, 2016). This is a brilliant work rooted in the newspapers of the era surrounding the US War of Independence. Parkinson demonstrates that persistent ideas of “white”, “Indian”, and “black” were created in the context of the British Crown encouraging Indigenous allies and slave uprisings during the war.

Peers, Michael, Apology to Native People: A message from the Primate, Archbishop Michael Peers, to the National Native Convocation, Minaki, Ontario, Friday, August 6, 1993, from https://www.anglican.ca/tr/apology/, accessed November 21, 2018.

Pennington, Loren E., “The Amerindian in English Promotional Literature 1575-1625” in The Westward Enterprise: English Activities in Ireland, the Atlantic, and America 1480-1650 edited by K. R. Andrews, N. P. Canny, and P. E. N. Hair (Liverpool UK: Liverpool University Press, 1978), pp. 175-194. Pretty much every aspect of English and British colonization in North America was tried first in the plantations of Ireland in the 16th century.

Proceedings of the Church Missionary Society Annual Sermons and Reports from North-West Canada Missions and British Columbia Missions in 1869, 1894, 1897, 1903, 1915. Archives of the Diocese of New Westminster, Vancouver BC.

Ranger, Terrence , “Christianity and the First Peoples” in Indigenous Peoples and Religious Change (Studies in Christian Mission) edited by Peggy Brock (Leiden NL: Brill, 2005), pp. 15-32.

Ray, Arthur J., An Illustrated History of Canada’s Native Peoples: I Have Lived Here Since the World Began, 2nd Edition (Toronto ON: Key Porter Books, 2005).

Regan, Paulette, Unsettling the Settler Within (Vancouver BC: University of British Columbia Press, 2010). A settler researcher for the Canadian Truth & Reconciliation Commission reflects on the need to rewrite history.

Report of the Executive Committee to the Synod of the Diocese of New Westminster, 1901. Archives of the Diocese of New Westminster, Vancouver BC..

Robertson, Leslie A., with the Kwagut’ł Gixsam Clan, Standing Up with Ga’axsta’las: Jane Constance Cook and the Politics of Memory, Church (Vancouver BC: University of British Columbia Press, 2012).

Robinson, Andrew, Lost Languages: The Enigma of the World’s Undeciphered Scripts (New York NY: Thames & Hudson, 2009). More interested in scripts than Indigenous justice, the book has chapters of Mayan writing and the Inca string records.

Royal Proclamation 1763, https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1370355181092/1370355203645, accessed November 13, 2017. The Royal Proclamation is the foundation of Indigenous rights in British/Canadian law.

Said, Edward W., Orientalism (25th Anniversary Edition) (New York NY: Vintage Books, 1994). Another classic in post-colonialism.

——————, Culture and Imperialism (New York NY: Vintage Books, 1994).

Scotland, Nigel, “John Bird Sumner in Parliament”, Anvil Vol. 7, No. 2, 1990. John Bird Sumner was an evangelical Archbishop of Canterbury in the middle of the 19th century, and among other things was an advocate of laissez faire political policies. Thus, he considered poverty and famine (including the Great Famine in Ireland) as part of the natural order.

Scott, Duncan Campbell, National Archives of Canada, Record Group 10, volume 6810, file 470-2-3, volume 7, pp. 55 (L-3) and 63 (N-3). Scott used to be best known as a poet, but he is now better known as the deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs in the first half of the 20th century, and the administrator of its racist policies.

Sepúlveda, Juan Ginés de, Demócrates, Segundo o las justas causas de la guerra contra los indios edited by Angel Losada (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientifícas, Institutio Francisco de Vittoria, 1951), quoted and translated in Lewis Hanke, All Mankind is One: A Study of the Disputation Between Bartolomé de Las Casas and Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda in 1550 on the Intellectual and Religious Capacity of the American Indians (DeKalb IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1974).

Slattery, Brian, “Paper Empires: The Legal Dimensions of French and English Ventures in North America” in John McLaren, A. R. Buck, and Nancy E. Wright, Despotic Dominion: Property Rights in British Settler Societies (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2005). This article clarifies how the Doctrine of Discovery actually played out.

Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, The Mission Field 1862, 1863, 1870. Archives of the Diocese of New Westminster, Vancouver BC.

Special Fund Obtained During a Ten Months’ Appeal by the Bishop of Columbia since his Consecration in Westminster Abbey on the Twenty-Fourth of February, 1859, with a Statement of the Urgent Need Which Exists For Sympathy and Support in Aid of The Columbia Mission (London UK: R. Clay, 1860), from the Archives of the Ecclesiastical Province of British Columbia & Yukon.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty, “Can the Subaltern Speak”, Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader, edited by Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman (New York NY: Columbia University Press, 1994), pp. 66-111. Yet another classic text in the post-colonial canon.

Stanley, Brian, The World Missionary Conference 1910 (Grand Rapids MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2009).

Sumner, John Bird, Treatise on Creation, Vol. II, quoted in Nigel Scotland, “John Bird Sumner in Parliament”, Anvil Vol. 7, No. 2, 1990.

Swanky, Tom, The True Story of Canada’s “War” of Extermination on the Pacific plus The Tsilhqot’in and Other First Nations Resistance (Burnaby BC: Dragon Heart, 2012). The article documents what was, at best, a reckless disregard by British colonial authorities for spreading disease among Indigenous communities, and at worst, was a deliberate policy of germ warfare.

Tharoor, Shashi, Inglorious Empire – What the British Did to India (London UK: Hurst Publishers, 2017). An expanded argument made at the Oxford Union on the devastating legacy of colonialism in India.

The Bishop’s Address to the Synod of the Diocese of New Westminster, 1902., Archives of the Diocese of New Westminster, Vancouver BC.

The Mission Field Vol. VII, April 1, 1862 from the Archives of the Ecclesiastical Province of British Columbia & Yukon.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Volume One: Summary. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future (Toronto ON: James Lorimer & Company, Ltd: 2015).

Thielen-Wilson, Leslie, “Troubling the Path to Decolonization: Indian Residential School Case law, Genocide, and Settler Illegitimacy” in Canadian Journal of Law and Society/Revue Canadienne Droit et Société Volume 29, no. 2, pp. 181-197.

Tinker, George, “The Full Circle of Liberation: An American-Indian Theology of Place” in Ecotheology: Voices North and South edited by D. C. Hallman (Geneva CH: WCC Publications, 1994), 218-226. Tinker is an Indigenous theologian.

——————, “Towards an American Indian Indigenous Theology”, The Ecumenical Review (12/2010, Volume 62, Issue 4), pp. 340-351.

——————, “Decolonizing the Language of Lutheran Theology: Confessions, Mission, Indians, and the Globalization of Hybridity”, Dialog, 2011, Volume 50, Issue 2.

Travis, Sarah, Decolonizing Preaching The Pulpit as Postcolonial Space (Eugene OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2014).

Tucker, L. Norman, Handbooks of English Church Expansion: Western Canada (Toronto ON: The Musson Book Company Limited and London UK & Oxford UK: A.R. Mowbray & Co. Ltd., 1908).

Tuhiwai Smith, Linda, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, Second Edition (London UK: Zed Books, 2012 and Dunedin NZ: Otago University Press, 2012). Mostly concerned with how Indigenous scholars, activists, and communities can decolonize, it also has significance for settler peoples and those trying to deal with the legacy of imperialism.

Twells, Alison, The Civilizing Mission and the English Middle Class, 1792-1850: The “Heathen” at Home and Overseas (Basingstoke UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

Twiss, Richard , Rescuing the Gospel from the Cowboys: A Native American Expression of the Jesus Way, edited by Ray Martell and Sue Martell(Downers Grove IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015). Another Indigenous Theology.

UN Convention on Genocide (1947), http://www.hrweb.org/legal/ genocide.html, accessed on May 22, 2017.

University of Victoria, Faculty of Law, https://www.uvic.ca/law/admissions/jidadmissions/index.php, accessed April 20, 2024. The Faculty of Law at UVic now offers a Joint Degree Program in Canadian Common Law and Indigenous Legal Orders, the first of its kind.

Urton, Gary, Inka History in Knots: Reading Khipus as Primary Sources (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2017). The definitive text in the Incan record system.

Varacalli, Thomas Francis Xavier, “The Thomism of Bartolomé de Las Casas and the Indians of the New World” (2016). Louisiana State University Doctoral Dissertations. 1664. http://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1664

Vickers, Patricia, Ayaawx (Ts’mseyn ancestral law): the power of Transformation unpublished doctoral dissertation (Victoria BC: University of Victoria, 2008).

Vowel, Chelsea , Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit issues in Canada (Winnipeg MB: HighWater Press, 2016). A great introduction.

——————, “A rose by any other name is a mihkokwaniy” <http://apihtawikosisan.com/2012/01/a-rose-by-any-other-name-is-a-mihkokwaniy/ >, accessed January 10, 2018.

Watson, Blake A., “The Impact of the American Doctrine of Discovery on Native Land Rights in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand”, Seattle University Law Review, Vol. 34, pp. 507-551

Watts, Joseph, Oliver Sheehan, Quentin D. Atkinson, Joseph Bulbulia, and Russell D. Gray, “”Ritual human sacrifice promoted and sustained the evolution of stratified societies”, Nature Vol. 532 (Apr. 14, 2016) pp. 228-231.

West, Gerald O., “Review of Grau, Marian, 2011. Rethinking Mission in the Postcolony: Salvation, Society and Subversion,” Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 146 (July 2013), pp. 170-171.

——————, “White Theology in a Black Frame: Betraying the Logic of Social Location”, Living on the Edge: Essays in Honour of Steve De Gruchy, Activist and Theologian, edited by James R. Cochrane, Elias Bongmba, Isabel A. Phiri and Desmond P. van der Water (Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 2012).

Williams, Jr., Robert A., The American Indian in Western Legal Thought: The Discourse of Conquest (New York NY: Oxford University Press, 1990). This landmark book was the first to root American law in Christian political theology of the Medieval era.

Winthrop, John, General Observations (1629),p. 113, quoted in Nicholas Guyatt, Providence and the Invention of the United States, 1607–1876 (Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Wiseman, Travis, “Slavery, Economic Freedom, and Income Levels in the Former Slave-exporting States of Africa” Public Finance Review 2018, Vol. 46(2) pp. 224-248.

Woodley, Randy S., Shalom and the Community of Creation: An Indigenous Vision (Grand Rapids MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2012). Another Indigenous theology.

Woolford, Andrew ,“The Next Generation: Criminology, Genocide Studies and Settler Colonialism” in Revista Critica Penal y Poder 2013, No. 5 (September), 163-185.

World Missionary Conference, 1910: Reports of Commissions I-VIII and vol. IX The History and Records of the Conference together with Addresses Delivered at the Evening Meetings (Edinburgh & London: Oliphant, Anderson, and Ferrier; and New York, Chicago, and Toronto: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1910). Yellow Bird, Michael, Indigenous Social Work (Aldershot UK: Ash